Books to Gift the Temperamentally Political

A short winter list for readers who see the world in layers rather than headlines. These are books that travel well across arguments, histories, and uneasy times.

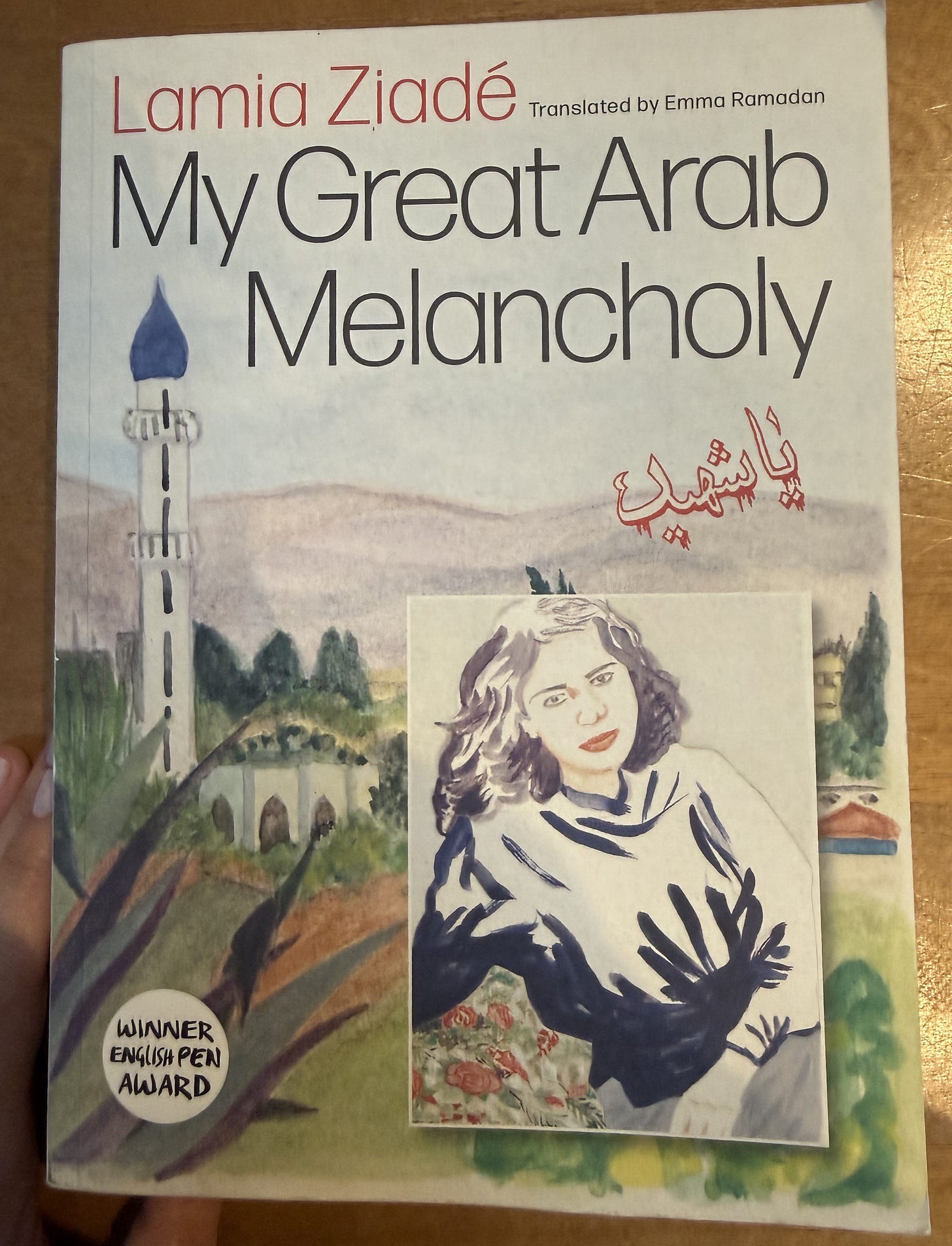

My Great Arab Melancholy, Lamia Ziadé

Ziadé brings an unusual combination to the modern Arab story: the eye of a visual artist, the memory of someone raised amid the Lebanese Civil War, and the discipline of a researcher who has spent years tracing the region’s political and emotional ruptures. The result is a memoir-archive hybrid where illustrations carry as much weight as the prose, and where the history of Beirut, Jerusalem, Cairo and Baghdad is told through the derailed ambitions that shaped them. She writes with quiet fury about imperial interventions and the long afterlife of Palestine’s dispossession while remaining attentive to the revolutionary imagination that once animated the Arab world. I recommend it because it gives readers a way to feel the history without drowning in sentiment. It is also an exquisitely made book, the kind you end up keeping out on the table.