Have you ever listened to a Syrian refugee talk about home?

What does it mean to lose a home—and to remake one? For millions of Syrians, home is no longer a given but something they must fight for, redefine, and rebuild. What is 'home' for you?

When we talk about Syria these days, we talk about geopolitics. Power plays, elite maneuvering, shifting alliances. We carve out pockets of politics, extrapolate them, and map the trajectory of the country from the top down. I do it too—because understanding the structures of power often tells us how the rest will fall into place.

But sometimes—perhaps more than sometimes—it’s necessary to pause, shift the frame, and change the lens. If understanding is truly the goal, there’s no other way.

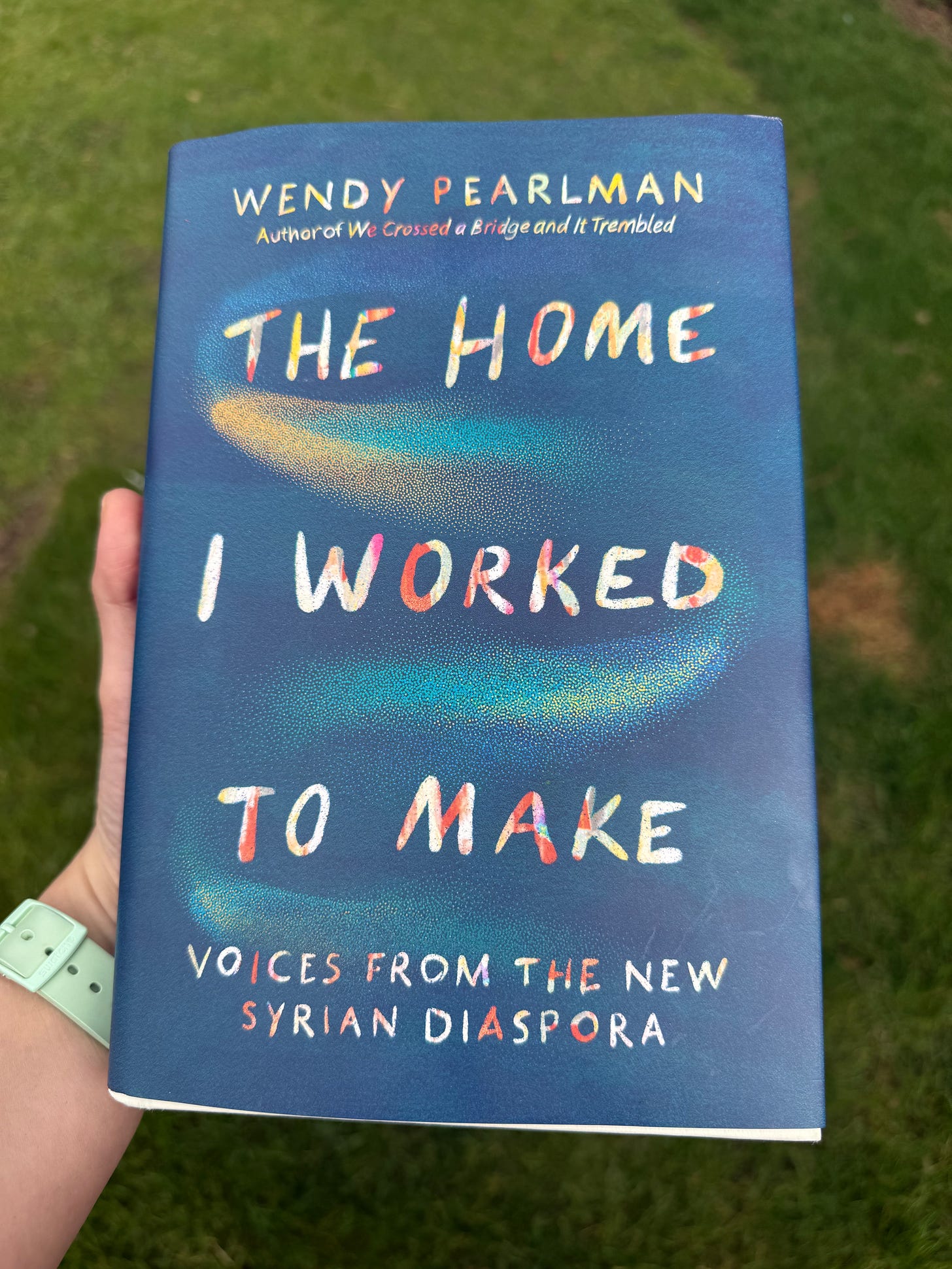

Wendy Pearlman’s book, The Home I Worked to Make: Voices from the New Syrian Diaspora, tells a story of today. Not just about Syrian refugees, but about all of us who leave, who try to leave, who stay but feel stuck. Those who find that the home they once knew no longer feels like home. It’s about all of us who become talking points, bargaining chips at the table of elite politics. And it’s about those who never imagined leaving—whose small neighborhoods, extended families, and childhood friends once…