How did the unthinkable Iranian revolution become inevitable?

Protests across Iran have revived claims that the Islamic Republic is facing its greatest test yet. Let's look back at the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and explore why revolutions defy prediction.

Following the 95 hours of total media blackout, videos began to surface showing bodies in black bags piled on top of one another, while people walk past them with blank faces. My Iranian friends still cannot reach or speak to their families back home. Can you imagine? In this day and age.

Iranians have been protesting since the last days of 2025, with demonstrations spreading to more than 70 locations. What began in places like the Grand Bazaar, initially sparked by everyday economic shocks, the sudden collapse of the currency, the price of basic goods such as eggs reportedly jumping by 300 percent in a single day, scale shifted, to borrow the language of contentious politics, into a nationwide revolt. It now involves all segments of society, though it is driven above all by the young, teenagers from 15 upwards, who have taken to the streets fully aware of the risks involved.

Iranian people, whom I believe to be among the bravest and most dignified, have taken to the streets again, knowing that this may heavily harm or end their lives. They have been on the streets since 2009, first demanding reforms, and then, in the last several years, loudly and clearly calling for regime change. They have been met with heavy crackdowns.

Now it is being propagated in Western media that this is the biggest challenge the theocratic Iranian regime has faced since it assumed power through a revolution. The mollah regime, long portrayed as invincible, may be meeting its end. There are reports that some elites linked to the regime and the IRGC (Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps) are preparing their exit plans, that gold is being smuggled out of the country, and that this time is different because the Iranian regime’s regional backers, Assad in Syria, are gone and Hezbollah in Lebanon is pacified. And that this time, the US president is ready to intervene to help collapse the regime.

Maybe. Maybe not.

We cannot know. That is the point of liminal moments such as these. There is too much contingency and too many confounding variables to be a political clairvoyant. What we can do, though, is look at past revolts and revolutions and try to come up with several explanations. This is what I am going to do with the help of a seminal work, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, by Charles Kurzman, a professor of sociology and an expert on social movements.

Everything Looked Fine

Remember the American National Intelligence chief back during Obama’s term who claimed that the Middle East had never been so quiet and calm. A few months later, Tunisians took to the streets en masse and the Egyptians followed, collapsing 2 authoritarian regimes, Ben Ali’s and Mubarak’s. Mubarak was preparing his son Gamal for succession while Ben Ali was filling his coffers just before they fell. A similar pattern can be seen during one of the 20th century’s most pivotal events, the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

In late 1978, the consensus among global intelligence experts was clear. The Iranian monarchy was secure. The Pahlavi dynasty, backed by billions in oil revenue and one of the world’s most formidable militaries, seemed unshakable. A report from the US Defense Intelligence Agency predicted that Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi “is expected to remain actively in power over the next 10 years.” The CIA’s analysis was similarly confident, stating that the political situation would remain stable.

No, it was not only neo-Orientalist Americans who did not know what they were talking about. Even key figures within the Iranian opposition believed a full-scale revolution was impossible. Just months before the Shah’s government collapsed, for example, Mehdi Bazargan, a leading opposition figure who would later become the revolution’s first prime minister, met with Ayatollah Khomeini in Paris. Bazargan argued that the revolution was “unthinkable” and pushed for a gradual, “step-by-step” plan for reform. He was stunned by Khomeini’s calm certitude that total victory was near.

So, what happened? Why was Khomeini so confident? How did the unthinkable revolution happen? How did the invincible Shah of Iran fall? And how did mullahs led by Khomeini assume power?

You may be struck, as I was, by how familiar the process looks. The authoritarianism, corruption, and accumulating unrest of the years leading up to 1979 echo uncomfortably in the present. And there is something chilling in seeing how the Shah’s brutal crackdown on protests led by Khomeini’s followers in 1978–79 mirrors the clerical regime’s violence against protesters today.

The Start: The Iranians ‘Awakened(!)’

The Iranian Revolution did not begin with the sudden eruption of Islamist mobilisation in late 1977. Long before that moment, dissent had been brewing across different corners of society. Liberal professionals and intellectuals began to speak out publicly in early 1977, encouraged by the Shah’s limited liberalisation and pressure from the Carter administration on human rights. Their ambitions were modest and legalistic. They sought a constitutional monarchy, parliamentary elections, and reform rather than rupture. To their left, guerrilla organisations such as the Mojahedin-e Khalq and the Fedayeen had already reached their peak in the early 1970s, striking at a time when the regime seemed most entrenched rather than most vulnerable. Students, meanwhile, had for years turned universities and even high schools into sites of relentless agitation, though their activism rarely translated into mass support beyond campus walls.

What distinguished the Islamists was not that they acted first, but that they moved differently. Unlike liberals, who responded directly to openings created by the state, Islamist mobilisation began in earnest only after the Shah reversed course and repression resumed. The death of Ayatollah Khomeini’s son, Mostafa, in late 1977 provided a catalyst, but what followed was a deliberate effort to create momentum under adverse conditions rather than permissive ones.

Khomeini perceived the subsequent mourning protests as a signal that the nation was “awakened” and ready for revolt, even though most Iranians were not yet prepared to act.

The Shah’s “Weakness” Was a Coherent Strategy

A common historical narrative portrays the Shah as “vacillating” and “inconsistent” in his response to the growing protests, paralysed by indecision. This view, however, misses the underlying logic of his actions. The Shah was not acting randomly; he was deliberately executing a classic “carrot and stick” strategy, combining harsh crackdowns with public apologies and promises of reform.

A clear example unfolded in early November 1978. In response to widespread unrest, the Shah appointed a military government to flood the streets with armoured vehicles and clamp down on the press. At the same time, he delivered a televised speech in which he expressed sympathy for the movement, apologised for past mistakes, and promised to establish a national government and hold free elections.

There was a dual message to the population. Stop protesting and you will get concessions. Continue protesting and you will get killed. But instead of being perceived as subtle statecraft, the public saw it as a fatal sign of weakness. Nevertheless, the revolutionary fervour on the ground had already moved beyond the point where such classic tactics could work.

The Paradox of Repression: Violence Fueled the Uprising

While the Shah consistently vetoed extreme proposals from his hard-line generals, such as bombing the city of Qom or executing hundreds of clerics, his security forces still routinely used lethal force to break up protests. Instead of intimidating the populace into submission, this repression had the paradoxical effect of fueling the uprising.

The death toll from protests escalated dramatically, from 35 in the first 8 months of 1978 to 137 in December–January and 179 in January–February as the revolution reached its climax. Hospital records and doctor testimonies show that most of the wounds that reached hospitals were to the stomach and chest, which means the soldiers were shooting to kill.

However, each act of violence, rather than sowing fear, created more outrage and resolve. A powerful concept, known as az jan gozashteh (abandoning life, outraged to the point of no longer caring about one’s welfare), began to take hold. After witnessing the regime’s brutality against friends, relatives, or fellow citizens, many Iranians lost their fear of death and became even more committed to the revolution.

The opposition understood this dynamic so well that it circulated a hoax audio cassette of the Shah seemingly ordering his generals to shoot demonstrators. Their calculation was that Iranians would be more outraged than intimidated. This created a vicious loop in which the state’s primary tool for control, force, became the opposition’s most effective tool for recruitment.

The Tipping Point or the Scale Shift

For the vast majority of Iranians, the decision to join the protests was not purely ideological. It was a pragmatic calculation based on a simple but powerful factor, the perceived number of other participants. Before the fall of 1978, protesting was an act for the deeply committed few. As the crowds grew, the risk for each individual appeared to diminish, creating a sense of safety in numbers.

A state’s power of coercion is like a bank’s cash reserves. It works as long as demands are limited. But when there is a run on the bank, yani when the entire customer base demands its money at once, the bank collapses. When the masses want change simultaneously, the state’s reserves of coercion are quickly overwhelmed. The more people, the less fear.

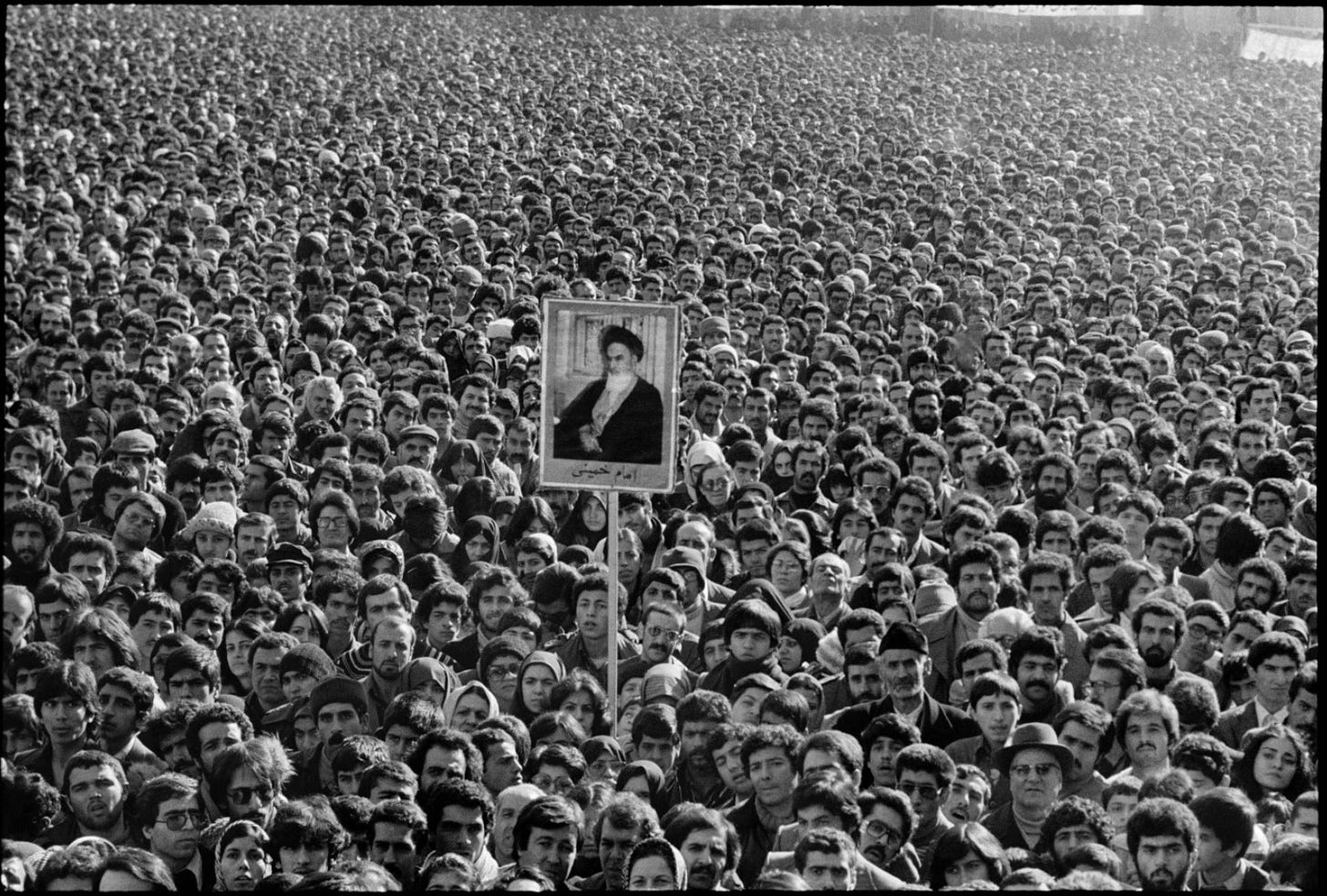

Once the protests grew large enough, the movement became viable in the minds of ordinary people. In other words, the belief that the revolution had a realistic chance of success became a self-fulfilling prophecy, drawing millions of previously cautious citizens into the streets. This critical mass was reached during the holy days of Ashura in December 1978, when marches across the country involved more than 10 percent of Iran’s entire population, probably the largest protest in history.

From Deep Distrust to Sudden Solidarity

Life in Pahlavi-era Iran was characterised by a pervasive climate of social mistrust, actively encouraged by the Shah’s security police, SAVAK. The fear was so ingrained that people worried “even your brother might be a SAVAK agent.”

This atomised, fearful society was transformed by the revolution. As millions of people took to the streets together, they experienced what many described as euphoric feelings of solidarity. The revolution rewove the fabric of daily life. People stopped talking about topics that had come to seem frivolous and instead spoke obsessively about politics, striking up conversations with strangers on the bus or in the street.

In a society fractured by fear, the collective action of the revolution created an almost instantaneous and powerful sense of shared purpose. This sudden solidarity was not just a by-product of the revolution. It was one of the key forces that sustained it.

The Fragility of the “Inevitable”

The Iranian Revolution was not an inevitable historical event driven by predictable forces. It was a cascade of human decisions made under conditions of extreme confusion and uncertainty, where the future was suddenly and shockingly up for grabs. What seemed stable and permanent one month was unthinkable the next.

What ultimately mattered was not a grand plan or a single ideology, but the critical moment when millions of disconnected individuals simultaneously perceived the opposition movement as viable and decided to act together.

The Shah Fell and the Clerics Rise

The Political Explanation: An Opening for Change?

Political explanations argue that revolutions occur when authoritarian regimes weaken and create openings for opposition mobilisation. In Iran, President Jimmy Carter’s emphasis on human rights and the Shah’s brief liberalisation in 1977 appeared to lower the costs of dissent and encourage protest. Yet this account falters on timing. It does not add up chronologically. While liberal opposition figures responded to these openings, the Islamist movement mobilised only after the Shah reversed course and renewed repression. Rather than reacting to state concessions, Islamists acted on the belief that society itself had reached a revolutionary moment. Khomeini’s ‘awakened’ idea. Because of the mismatch of timing political opportunity structure framework alone cannot explain this dynamic.

The Organizational Explanation: The Power of the Mosque Network?

This can also be called the perceived ‘Islamist advantage’, which emphasises, for example in the case of the Muslim Brotherhood, its decades-long organisational structure of charity work, presence in unions, and reach in mosques. Let me say this clearly: this argument, the supposed advantage of Islamists, is often overestimated, because it does not always translate into mid- to long-term political and institutional legitimacy in a multiparty context.

For the 1979 revolution, the argument goes, Iran’s mosque network functioned as a ready-made infrastructure for mass mobilisation, giving Islamist actors a decisive advantage over secular groups. However, this network was not initially revolutionary. Many religious leaders were cautious and sought to avoid confrontation with the state. Throughout much of 1978, Islamists had to persuade, pressure those clerics and gradually take control of these institutions. The mosque network thus emerged as the result of mobilisation rather than its precondition.

The Cultural Explanation: A Shi‘i Revolution?

Cultural interpretations highlight the language, symbols, and rituals of Shi‘i Islam, particularly narratives of martyrdom and the use of religious calendars to sustain protest. Yet these traditions were not simply activated. More generally, constants are weak tools for explaining causation. Mourning rituals were politicised, and Muharram ceremonies were transformed into carefully managed mass demonstrations designed to minimise risk and attract hesitant participants. Culture mattered, but its revolutionary force lay in strategic reinterpretation rather than inherited meaning.

The Economic Explanation: A Revolt of Hardship?

Economic explanations point to rising expectations during the oil boom and their collapse during the 1977–78 recession, producing anger and disillusionment. While economic hardship was widely felt and frequently cited, it does not fully account for the revolution’s timing or composition. Earlier downturns had not produced similar outcomes, and the social groups most affected economically were not the most active in the uprising. Economic grievance contributed to unrest but cannot explain the scale or momentum of the revolution on its own.

The Military Explanation: A Failure of the Fist?

State-breakdown theories argue that the Shah’s illness, indecision, and reluctance to deploy overwhelming violence fatally weakened the regime’s repressive capacity. In reality, repression continued until the final days, with arrests, shootings, and military rule escalating violence. The problem was not lack of will but lack of capacity - the bank run situation. As protest and strikes multiplied, the state was overwhelmed by numbers it could no longer control, exhausting its coercive resources in the face of mass participation.

The “Anti-Explanation”

Rather than retroactively rendering the revolution inevitable, the anti-explanation foregrounds confusion and uncertainty as lived experiences. Decisions to protest were shaped by constantly shifting judgments about viability, driven by perceptions of safety in numbers. Individuals joined when they believed others would too, producing a self-reinforcing cycle in which participation reduced fear and increased the sense that victory was possible. In this way, the revolution did not unfold because it was predictable, but because collective belief gradually made it real.

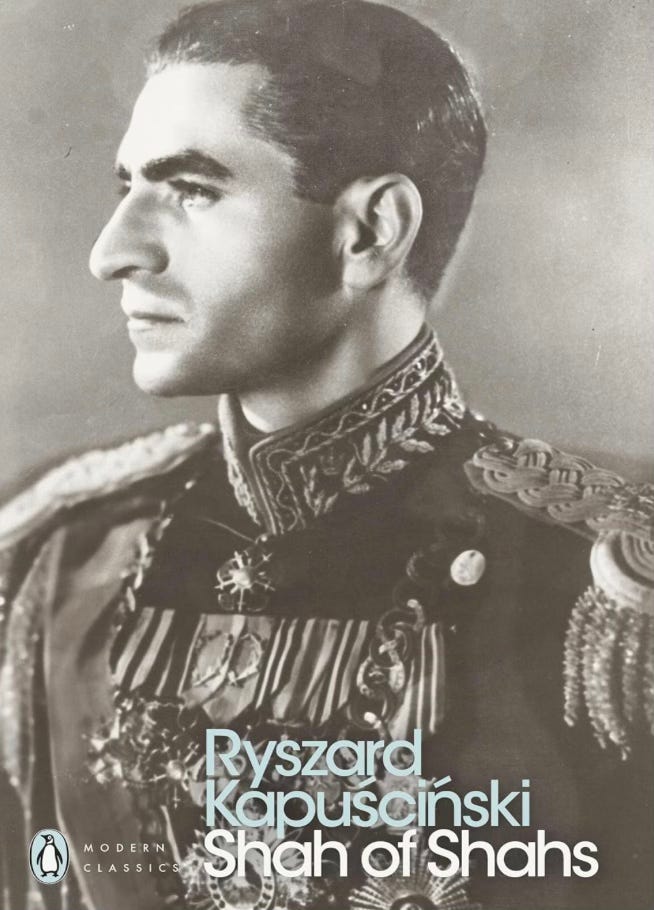

The long shadow of authoritarianism

I want to end this week with a reminder, and I can think of no better guide than the late Polish journalist and author Ryszard Kapuściński. As you will see, he says in simple words what I have been trying to explain in this piece through many words, frames, and theories. This is narrative non-fiction at its best.

Writing as a witness rather than a theorist in his book, Kapuściński looked at both ends of modern Iranian history: the Shah’s reinstatement after the CIA-backed coup that removed prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953, and his ousting in the 1979 revolution. What he captures, with remarkable clarity, is not just how power falls, but how it lingers, how language works on people long before streets fill, and how revolutions are prepared quietly, often unknowingly, over many years.

It is a beautiful book, attentive to words, silences, and misjudgements. Kapuściński reminds us that revolutions are not born only out of misery or repression, but out of consciousness, of the moment when people realise that what they endure is neither natural nor permanent. And that how words shape choices and how dictatorships cast long shadows long after they fall.

‘We were all writing protests, manifestos, letters, statements. Only a small group of intellectuals read them because such materials could not be printed legally and, besides, most people didn’t know how to read. We were criticizing the monarch, saying things were bad, demanding changes, reform, democratization, and justice. It never entered anyone’s head to come out the way Khomeini did—to reject all that scribbling, all those petitions, resolutions, proposals. To stand before the people, and cry, The Shah must go! That was the gist of what Khomeini said then, and he kept on saying it for fifteen years. It was the simplest thing, and everyone could remember it—but it took them fifteen years to understand what it really meant. After all, people took the institution of the monarchy as much for granted as the air. No one could imagine life without it. The Shah must go! Don’t debate it, don’t gab, don’t reform or forgive. There’s no sense in it, it won’t change anything, it’s a vain effort, it’s a delusion. We can go forward only over the ruins of the monarchy. There’s no other way. The Shah must go! Don’t wait, don’t stall, don’t sleep. The Shah must go! The first time he said it, it sounded like a maniac’s entreaties, like the keening of a madman. The monarchy had not yet exhausted the possibilities of endurance (p.42).’

‘The Shah left people a choice between Savak and the mullahs. And they chose the mullahs. When thinking about the fall of any dictatorship, one should have no illusions that the whole system comes to an end like a bad dream with that fall. The physical existence of the system does indeed cease. But its psychological and social results live on for years, and even survive in the form of subconsciously continued behavior. A dictatorship that destroys the intelligentsia and culture leaves behind itself an empty, sour field on which the tree of thought won’t grow quickly. It is not always the best people who emerge from hiding, from the corners and cracks of that farmed out field, but often those who have proven themselves strongest, not always those who will create new values but rather those whose thick skin and internal resilience have ensured their survival. In such circumstances history begins to turn in a tragic, vicious circle from which it can sometimes take a whole epoch to break free (p.58).’

‘The revolution put an end to the Shah’s rule. It destroyed the palace and buried the monarchy. It all began with an apparently small mistake on the part of the imperial authority. With that one false step, the monarchy signed its own death warrant. The causes of a revolution are usually sought in objective conditions—general poverty, oppression, scandalous abuses. But this view, while correct, is one-sided. After all, such conditions exist in a hundred countries, but revolutions erupt rarely. What is needed is the consciousness of poverty and the consciousness of oppression, and the conviction that poverty and oppression are not the natural order of this world. It is curious that in this case, experience in and of itself, no matter how painful, does not suffice. The indispensable catalyst is the word, the explanatory idea. More than petards or stilettoes, therefore, words—uncontrolled words, circulating freely, underground, rebelliously, not gotten up in dress uniforms, uncertified—frighten tyrants. But sometimes it is the official, uniformed, certified words that bring about the revolution (p.103).’