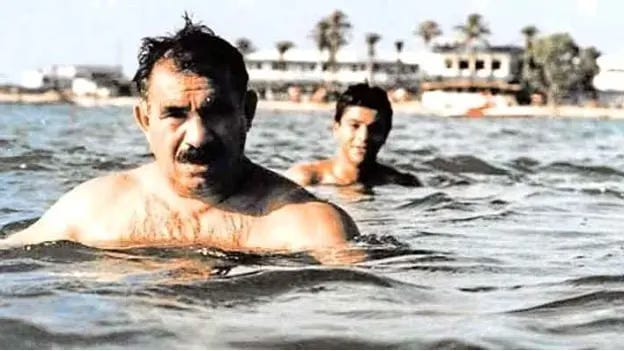

Öcalan's message to Syrian Kurds

What did Öcalan envision for the Syrian Kurds while calling on the PKK to disarm and disband? How would the Trump administration react? Is the Kurdish issue the new wedge between Israel and Turkey?

Öcalan’s call for the PKK to disarm and dissolve has triggered pressing questions about the Syrian Kurdish movement—specifically, the SDF, which governs Rojava and remains an offshoot of the PKK. SDF commander Mazlum Abdi, who spent his formative years alongside Öcalan and was once part of the PKK, was quick to clarify: the letter, he insisted, was directed at the PKK, not the SDF. Technically true—there was no explicit mention of the SDF in the statement. But that’s only part of the story.

Before the public reading of Öcalan’s message last week, he had already sent a separate letter to the SDF, a fact Abdi himself acknowledged. Two sources familiar with its contents say Öcalan praised the governance model in Rojava before offering strategic advice. First, he urged the SDF to establish itself as a legitimate political force within Syria—meaning institutionalizing as a political party and becoming a recognized stakeholder in the country’s governance. Second, he warned that demanding an independent military force in negotiations with Damascus was neither realistic nor necessary, especially if the SDF secured a strong political foothold.

To drive the point home, Öcalan pointed to Hezbollah. His message was clear: failing to merge into formal politics at the right moment carries serious risks. Hezbollah, he suggested, had miscalculated at critical junctures, setting itself on a path to decline. The SDF, he implied, should avoid that fate at all costs.

Unsurprisingly, Öcalan envisions a similar non-violent transformation for the SDF. But dismantling the PKK’s armed structure and integrating the SDF into Syria’s formal political system are monumental tasks—ones that require careful legal groundwork and, above all, time. Keeping this in mind is crucial to sustaining the morale needed for peace.

‘You don’t have to do what Americans say’

Former U.S. diplomat Peter Galbraith has been deeply immersed in Kurdish politics since the early 1990s. As I mentioned in an earlier piece, he was the first American official to report Saddam Hussein’s Halabja massacre and chemical weapons use to Washington.

I spoke with Galbraith, who is on a first-name basis with the leadership of the Kurdistan Regional Government and remains deeply engaged in Kurdish affairs across Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. Given his longstanding engagement, I asked for his perspective on the latest developments—particularly the imprisoned PKK leader’s call last week for the group’s dissolution and disarmament.

‘I firmly believe the PKK had nothing left to gain from waging war in Turkey. This has nothing to do with the merits of their cause but with the hard realities on the ground. Turkey is not Iraq or Syria. It is a strong state, and armed struggle achieves nothing there. The situation is markedly different for the Syrian Kurdish movement – the PYD.’

Galbraith has advised the Iraqi Kurds through pivotal moments, including constitutional negotiations with Baghdad and the 2017 independence referendum. He was also involved in the East Timor negotiations and has maintained ongoing discussions with Rojava’s leadership since Assad’s authority began unraveling.

‘Negotiations are not a carpet selling business. You have to be sincere in your demands and go with what you want, not with less. There’s a Kurdish tendency to engage in preemptive surrender. That’s unnecessary. At the same time, one must be prepared for trade-offs. The SDF will be negotiating with Damascus over taxation, investment, resource management, local security, and lawmaking. The key is meticulous preparation—knowing precisely what future you envision.’

The PKK’s exit, Galbraith noted, would be welcomed by Iraqi Kurdistan. ‘I remember both Barzani and Talabani resenting the PKK’s presence in Dohuk. It put them under Turkish pressure, and they felt the PKK leadership was needlessly dismissive of them. The KRG kept its distance from the SDF due to its PKK ties, but alliances shift with circumstances. We’ve already seen how Masoud (Barzani – former president of the KRG), Masrour (prime minister of the KRG), and Nechirvan (Barzani – the President of KRG) were involved in both Turkey-Öcalan and SDF-Damascus negotiations. If the PKK dissolves, the KRG will be more friendly with the Syrian Kurds.’

As for Washington’s response, Galbraith is skeptical. ‘I have no idea how the Trump administration would react to these shifts. The way things are going, it seems preoccupied with betraying Ukraine and depopulating Gaza—Kurds are likely low on their list. But I’ve told the SDF, and I’ve told both Jalal (Talabani – 6th president of Iraq 2005-14) and Masoud multiple times: You don’t have to do what the Americans on the ground say. These field operatives often take liberties, creating more confusion than clarity. I see much of what happened under US special envoy to Syria James Jeffrey in this light. The SDF must understand that its future lies with Damascus, not blindly heeding American instructions.’

A New Wedge Between Israel and Turkey

A fresh rupture is emerging. Since October 7, tensions between Israel and Turkey have taken on a new dimension. Longtime regional partners turned uneasy rivals - adversaries? - , their relationship had already been strained—Erdogan’s 2009 ‘one minute’ rebuke, his open support for the Palestinian cause, high-profile meetings with Hamas figures like Khaled Meshaal, and the Mavi Marmara flotilla incident all accumulated into an elephant in the room. Both sides chose to ignore it, maintaining pragmatic ties—until now.

Israel’s relentless war, which has amounted to genocide, has prompted Erdogan to unleash his characteristic firebrand rhetoric, branding Israel a ‘terror state.’ That was expected. What was not was his claim that Israel might wage war against Turkey—a theory he repeated for weeks before it quietly faded. Meanwhile, in Israel, a government commission led by former National Security Council chief Jacob Nagel produced a report on the IDF’s strategic future, warning that ‘Turkey’s ambitions to restore its Ottoman-era influence could escalate tensions with Israel, possibly leading to direct confrontation.’

This fraught relationship is set for further turbulence as Israel tightens its grip on southern Syria. Originally framed as a ‘temporary’ incursion to neutralize Assad’s chemical arsenal, it has since expanded, with Israeli officials now openly stating they will indefinitely hold and demilitarize the zone. Repeated Israeli strikes are fueling instability, disrupting what little stability remains in Syria, and—unsurprisingly—provoking further friction with Turkey. Not just due to Israel’s physical proximity but because it is actively meddling in Kurdish affairs.

Israel has reportedly offered ‘protection’ to both the PKK and SDF—though the specifics remain unclear. What is clear is that this has something to do with countering Turkey’s presence in Syria. According to Reuters, Israel is lobbying the U.S. to ‘keep Syria weak and decentralized, including by letting Russia maintain its military bases there to curb Turkey's expanding influence.’ Another key demand? Blocking Turkey’s efforts to establish three new military bases under its recent agreement with Damascus.

Netanyahu framed it bluntly in his latest speech: ‘Extending our hand to our Druze allies and Kurdish friends in the region.’ Erdogan, never one to let a statement go unanswered, immediately fired back: ‘Those stirring ethnic and sectarian divisions to destabilize Syria will not succeed.’

The latest twist in this saga borders on the absurd: for the first time in its history, the IDF announced on Tuesday that it has launched a Turkish-language social media account. Really? But why?

Construction companies rush to Syria

Turkey’s engagement in Syria isn’t merely tactical or strategic—it’s economic. While military and geopolitical objectives take precedence, the economic dimension is waiting in the wings. That doesn’t mean Turkish businesses are sitting idly by.

Turkish construction firms are already eyeing opportunities to rebuild Syria. The Buildex construction fair, set for May at the Damascus Fairground, has attracted interest from Turkish, Egyptian, and Saudi firms—breaking years of Chinese and Russian dominance in the sector. Business delegations will return to Damascus for Turkish Construction and Energy Week in June. Meanwhile, Qatar has declared its intent to play an active role in Syria’s reconstruction.

As always, influence follows money. Whoever bankrolls the bulk of Syria’s redevelopment—whether Doha, Riyadh, Ankara, or Cairo—will hold significant sway over its future. Geography favors Turkey, given its 900 km border with Syria, but geography alone isn’t enough. Turkey may have the access, but it doesn’t necessarily have the financial muscle to dictate terms unchallenged. The competition will be fierce.