Turkey’s gamble with the Kurdish question in Syria

I spoke with one of the top politicians of the Syrian Kurds—here’s the current state of affairs and its broader implications.

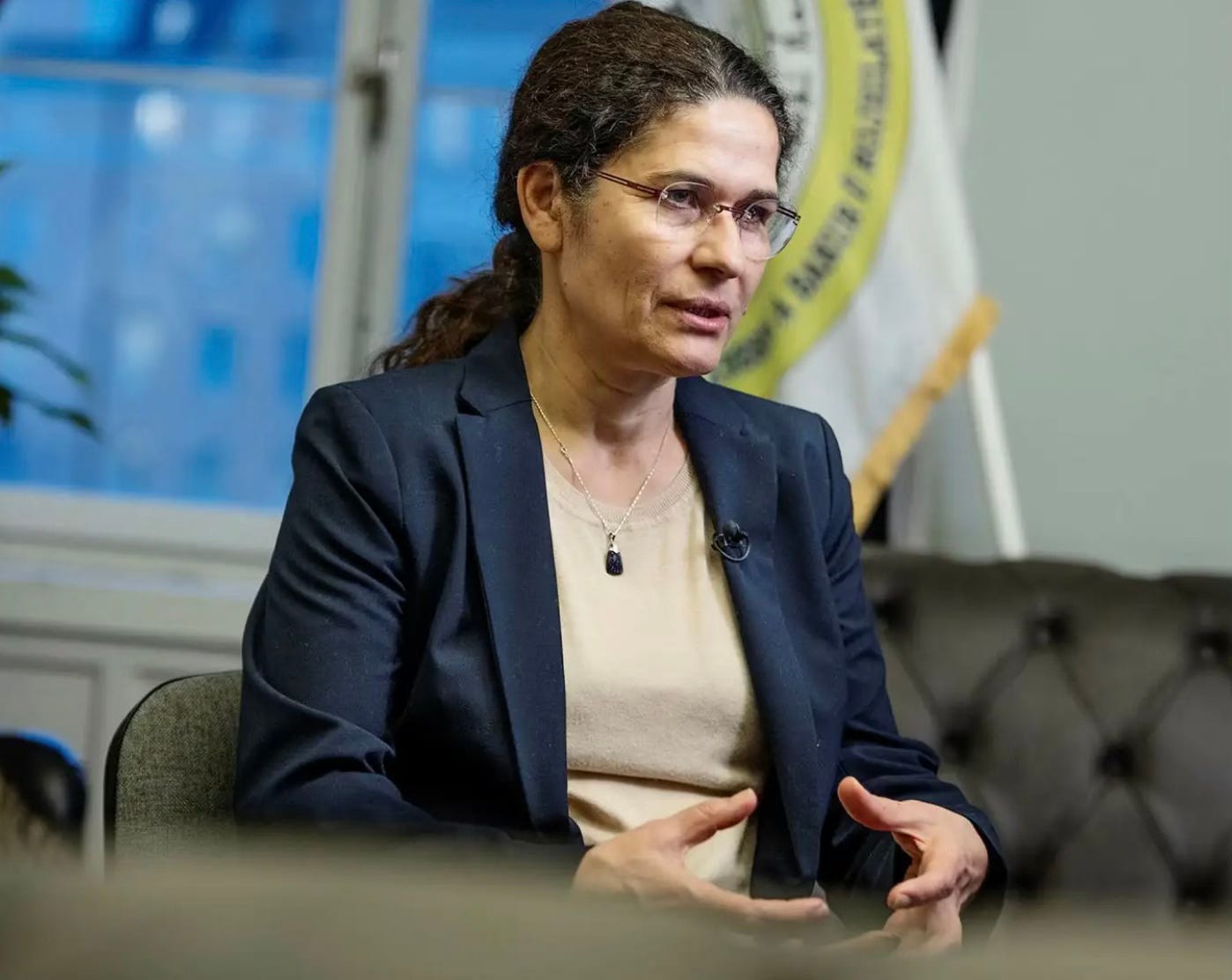

A couple of days ago, I had the opportunity to meet and spend time with some members of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—the Kurdish-led group governing northeast Syria, known as Rojava or Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES)—including Ilham Ahmed, their de facto foreign minister. Ahmed is an astute and poised politician, deeply attuned to the complexities of Syria and the wider region.

Let me share what I learned from them about their primary obstacles, objectives, and aspirations for the near future.

The main challenge

Turkey remains their foremost obstacle. Through its influence over the interim HTS government, led by Ahmad al-Sharra, and its direct military offensives against Kurdish-controlled areas, Turkey maintains relentless pressure on the SDF.

The SDF also bel…