Academics and Students Who Are on the Right Side of History

This moment will be remembered. As it darkens, some will rationalize, some will look away. Others will speak—and pay the price. But only one side will be remembered as the right side of history.

“Aid has dried up and the floodgates of horror have re-opened. Gaza is a killing field, and civilians are in an endless death loop,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres declared in early April. A couple of days ago, he described the situation in starker terms: a humanitarian emergency “beyond imagination.”

A friend of mine tried to capture it: “Gaza looks like Mars.” Something otherworldly. As if it no longer belongs to human history or human making. But Gaza is on this earth—and it has been reduced to rubble. No food. No water. No air. No future.

Guterres went further: “I am alarmed by statements from Israeli officials suggesting aid is being used as leverage for military gain. Aid is not a bargaining chip. It is non-negotiable.”

He urged governments to move beyond hollow declarations and set out actual steps to revive the long-abandoned two-state framework. “This is not a time for box-ticking,” he said. “The clock is ticking—and time is running out.”

One cannot help but ask: how is it that, on an issue so elementary—pure, unadulterated human suffering—we find ourselves incapable of consensus? This is not a morally complex dilemma. It is a textbook case of collective punishment, a crime against humanity livestreamed to the world. And yet, the global ‘liberal’ conscience splits down the middle.

It is only the Palestinian question that can cleave the so-called “international community”—that euphemism for the West and its allies—into such incoherent halves. Self-declared liberals, democrats, progressives, the bearers of universal norms, the instructors of human rights—divided. Only some are on the right side of history.

Why? Because what is unfolding in Gaza is not merely a geopolitical tragedy. It is the aftershock of colonialism and the counter-violence of incomplete decolonization. The violence of the norm-setters has been made visible—and they cannot bear the sight of themselves.

Those who have dared to oppose it—who have raised their voices, however gently—are now being punished. Students and scholars are facing surveillance, detention, travel bans, and professional exile. Visas are revoked. Entry is denied. Conference invitations become liabilities. A growing number of academics now fear leaving the United States for fear they will not be allowed to return. One colleague put it plainly: we are “de facto imprisoned and deemed voiceless.”

Jewish organizations that have supported these students and faculty face their own forms of persecution—smears, doxxing, denunciation by Israeli state-affiliated networks, and accusations of being “self-hating.” But their solidarity is an act of moral courage. Chapeau to all of them.

The majority of those targeted are scholars of the Middle East—people who have dedicated their lives to studying the histories, literatures, and political trajectories of the region. They now find themselves at the centre of a coordinated campaign of vilification. At Harvard and Oxford, two of the world’s leading Middle East centres have been embroiled in parallel controversies.

At Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Professors Cemal Kafadar and Rosie Bsheer were forced to step down last month, following a barrage of accusations of “anti-Israel bias.” In Oxford, the Middle East Centre at St Antony’s College, long led by Professor Eugene Rogan, has faced a similar attempt to discredit it—coalescing around the same network of actors, levelling the same cynical charges.

One Harvard colleague called it what it is: a disgraceful attempt to appease Trumpist rage. Oxford, thanks to its federal structure, has so far withstood the pressure, and the UK remains—by comparison—a more common-sensical polity. But that does not mean dissent comes without consequence. Academics here are no more insulated from the tightening atmosphere of fear and silence.

This moment will be remembered. As it darkens, some will rationalize, some will look away. Others will speak—and pay the price. But only one side will be remembered as the right side of history.

Trump’s 100 days and Erdogan’s 2016 coup

I recently listened to a compelling episode of Prospect magazine’s podcast, in which the brilliant senior editor Alona Ferber and Ellen Halliday spoke with Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a leading scholar of authoritarianism, about Trump’s first 100 days. Ben-Ghiat raised a question that many of us—scholars and citizens of Middle Eastern polities—have been asking each other with a sense of disbelief: what explains the speed of authoritarian consolidation under Trump? Erdoğan took years, even a decade, to begin the descent into full-blown authoritarianism. Putin, too, encountered several structural and political hurdles. Yet in what is often mythologized as the world’s most established democracy, Trump’s authoritarian offensive is unfolding in record time—barely 100 days.

Ben-Ghiat herself finds the velocity remarkable, even as a seasoned analyst of strongmen. Her argument is twofold. First, when figures like Trump return to power after a political hiatus, they often do so with a vengeance—and with a plan. Because Trump never conceded the 2020 election, he preserved his personality cult intact and used the interregnum to build his infrastructure of return. That included aligning with Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation-backed blueprint that his administration began enacting almost immediately in January.

Second, Ben-Ghiat suggests we read Trump’s first 100 days not as mere policymaking, but as the postscript to a coup—what typically follows once a power grab has succeeded. She draws a parallel to Erdoğan’s purges following the botched 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, when the judiciary, bureaucracy, and security services were swiftly gutted and reengineered.

I find the coup analogy apt. But we must also remember: for a post-coup climate to emerge, the political terrain must first be poisoned, the institutions hollowed out. Trump may be the culmination—but he is also the consequence. You don’t get someone like Elon Musk parachuting into the halls of power unless a crony-capitalist, oligarchic order has already been normalized.

That said, I highly recommend the Prospect podcast episode, and Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s excellent Substack, Lucid, for sharp analysis.

5000 Years of Gaza

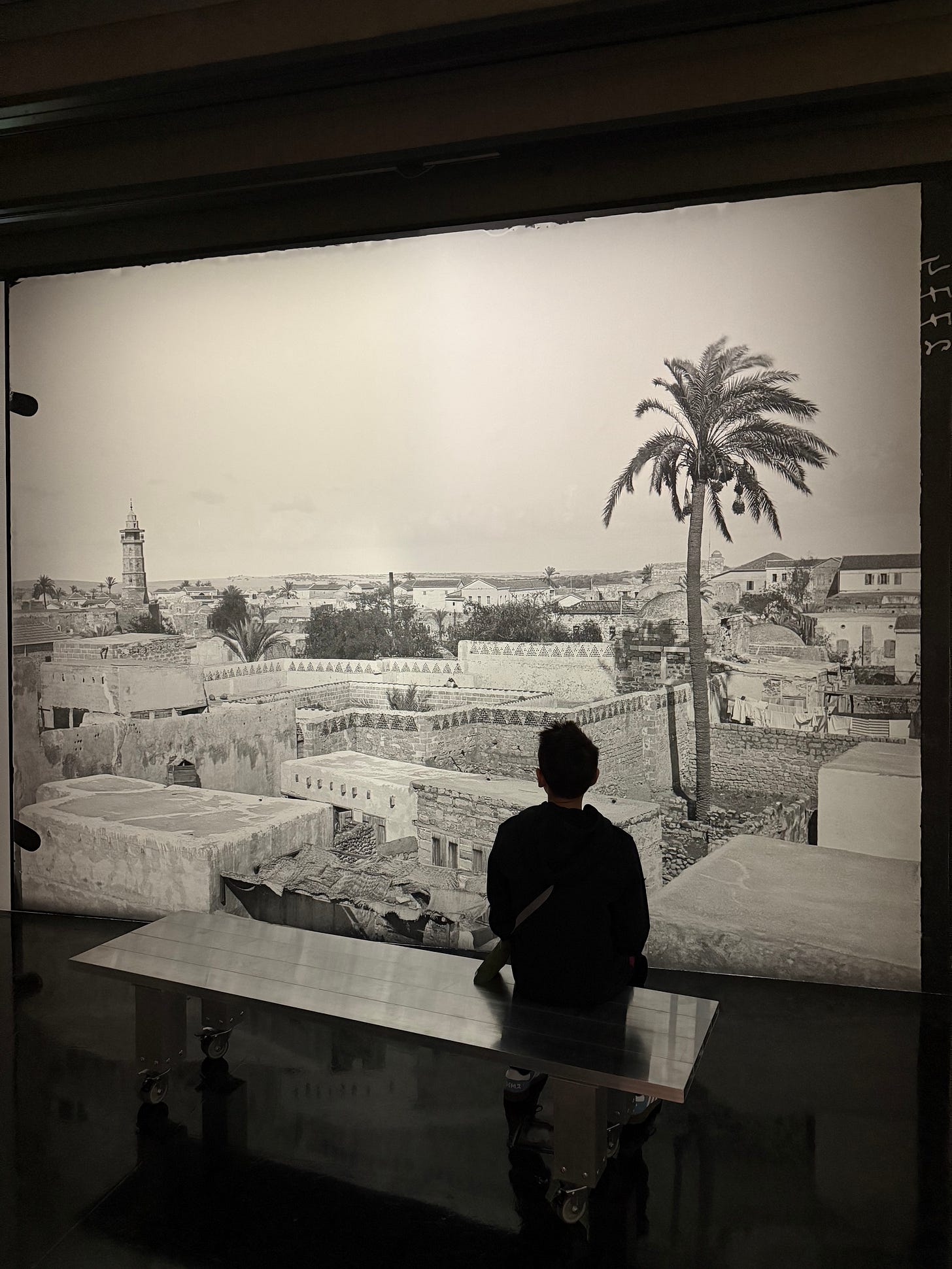

Before it became a death camp that resembles a Martian crater, Gaza was something else.

An oasis of trade and civilisation, Gaza has long stood at the intersection of empire. From the rivalry between Nile and Euphrates to the Mediterranean’s southern rim, Gaza was both prize and conduit—coveted by Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Crusaders, Mamluks, Ottomans. Strabo called it “the greatest city of Syria.” It was a port of passage and a caravan hub linking Africa, Arabia, and India. Its strategic and symbolic value made it one of the most contested places in history.

This is what centuries of colonial warfare and decades of occupation have obscured. Gaza’s ancient cosmopolitanism has been buried—deliberately—in the rubble of modern destruction.

That’s why I made a point of visiting Gaza: 5000 Years, the exhibition currently on show at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris.

The exhibition displays fragments of a culture under siege—artifacts that escaped war, siege, and neglect. Since 2007, the Museum of Art and History in Geneva has hosted nearly 530 archaeological pieces belonging to the Palestinian National Authority—amphorae, oil lamps, figurines, funerary steles, mosaics—ranging from the Bronze Age to the Ottoman era. These objects have never returned to Gaza, but they form an archive of endurance.

With support from the MAH and the PNA, the IMA has assembled a selection of 130 works: excavated since the 1990s through Franco-Palestinian efforts, including the extraordinary mosaic of Abu Baraqeh, and pieces from the private collection of Jawdat Khoudary, donated in 2018 and now displayed in France for the first time.

Alongside these works are bombing maps compiled by research groups, a timeline of recent archaeological finds, and rare photographs of Gaza from the early 20th century. But the exhibition’s most important contribution lies elsewhere: it reasserts Gaza’s historical centrality. It testifies to a continuity of civilisation that refuses erasure.

Do visit if you find yourself in Paris. History matters. Especially now.

Note to readers: I love when our conversations continue in the comments. Let’s meet there and push the debate forward. Hugs and kisses. Ezgi.

It’s not helped by many of the newspapers, at least in the UK, being pro-Zionism. Many of my Muslim friends boycott US companies in protest of Gaza / the US regime. If more people did it would help. In corporations where money is the only god, reduction of the bottom line hurts.

I just wanted to thank you for this post! I am sure many people share your and my opinion - that it is just enough... What happens there is (and I am for a two-state-solution and I abhor and fully ackknowledge the terrorism from the Hamas-side) state-funded genocide/terrorism and nothing else... It just has nothing to do with defense or war - it is ruthless, careless murder. And it is what the radicals on both sides want - escalation. It is what no sensible human being can accept. I don't know how this can be stopped - I don't believe in boycotting a country but I cannot believe that so many people in charge in several countries look away. Thanks, dear Ezgi!