The idea of a Jewish homeland and the objection of Britain’s only Jewish minister

In 1917, Britain cast its guilt into policy by pledging a home for the Jews in Palestine. The only Jewish minister in the Cabinet Edwin Montagu tried to stop it. Why?

The Balfour Declaration was drafted in the glow of wartime idealism and the shadow of imperial ambition. In 1917 Britain promised support for a Jewish “national home” in Palestine, imagining it as both an act of justice and a stroke of strategy. Yet the lone Jewish member of the Cabinet, Edwin Samuel Montagu, opposed it with fierce clarity, warning that Zionism would endanger Jews rather than redeem them. His dissent, soon drowned out by triumphal politics, reveals how the language of sympathy can conceal hierarchy and how the moral debts of Europe, left unpaid, still shape the politics of the present. In a previous post, I had promised to return to the Balfour Declaration in greater depth, and I now turn to one of the most meticulous accounts of its making and aftermath, The Balfour Declaration by historian Jonathan Schneer.

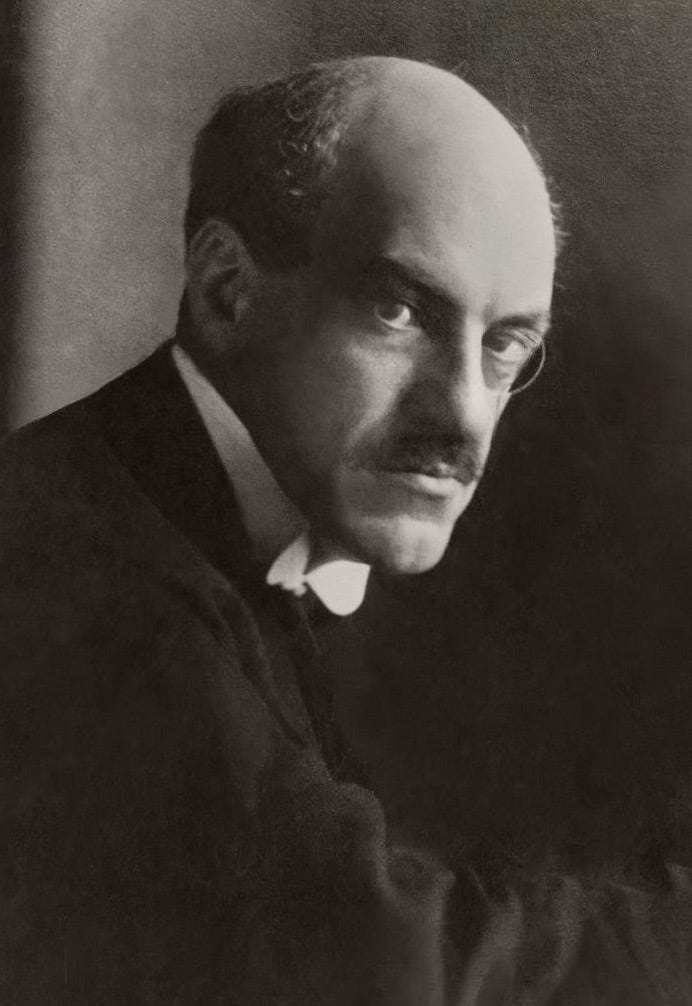

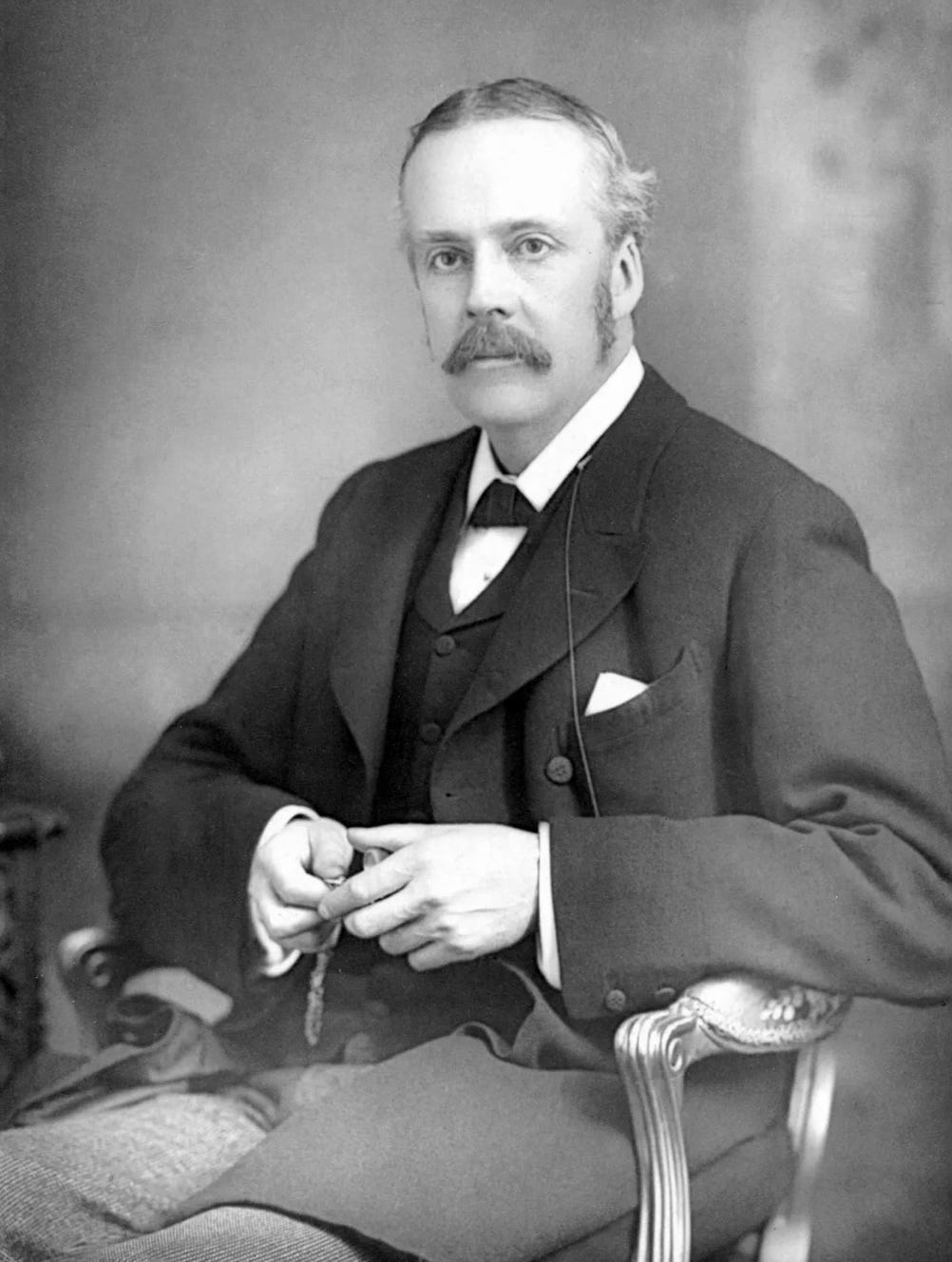

In November 1917, as the First World War ground through its fourth year, Britain issued a 67-word letter that would transform the politics of the Middle East and sharpen arguments about Jewish identity in Britain itself. The Balfour Declaration—authored by Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour and addressed to Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild—announced that “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” while adding safeguards for “non-Jewish communities” and for the civil and political status of Jews outside Palestine (Schneer, ch. 24). The text was the product of months of lobbying by Chaim Weizmann, Nahum Sokolow, and a tight circle of British Zionists; of wartime calculations by Prime Minister David Lloyd George; and of often-misguided beliefs among British officials about “world Jewry.” It also provoked the most forceful objection from the only Jewish member of the Cabinet, Edwin Samuel Montagu, the newly appointed Secretary of State for India, who warned that endorsing Zionism would harm Jews in Britain by re-nationalizing them as foreigners in the land they called home (Schneer, ch. 24).

Through the summer of 1917, Weizmann and Sokolow coordinated a methodical plan to draft a short, general statement the government could accept, route it through Lord Rothschild to Balfour, secure War Cabinet approval, and have Balfour return the commitment in a formal letter (Schneer, ch. 24). Meeting in London’s Imperial Hotel, a Zionist committee that included Sokolow, Israel Sieff, Simon Marks, Leon Simon, Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginzberg), and Harry Sacher reduced several maximalist drafts to two spare sentences. The architect of the final phrasing was Sacher, while Simon wrote the text on a scrap of paper that would surface at Sotheby’s nearly a century later (Schneer, ch. 24).

1. “His Majesty’s Government accepts the principle that Palestine should be reconstituted as the National Home of the Jewish people.”

2. “His Majesty’s Government will use its best endeavors to secure the achievement of this object and will discuss the necessary methods and means with the Zionist Organization.” (Schneer, ch. 24)

Montagu’s Objection

Crucially, sympathetic officials—Sir Mark Sykes at the War Cabinet Secretariat and Sir Ronald Graham at the Foreign Office—steered Zionists toward brevity and away from explicit statehood. Alfred, Viscount Milner softened “reconstituted” to “a National Home for the Jewish people,” and Leopold Amery added what would become the famous protective clause about not prejudicing the rights of non-Jews in Palestine, while also toning down references to the Zionist Organization as an official interlocutor (Schneer, ch. 24). These edits signaled cautious endorsement, not rejection.

The rejection came from Edwin Samuel Montagu, a cousin of Herbert Louis Samuel (who had earlier urged Cabinet sympathy for Zionism). Montagu had just re-entered government, first as minister without portfolio for postwar reconstruction and then as India Secretary, and when he finally saw the Zionist text and Balfour’s draft reply on 22 August 1917, he erupted (Schneer, ch. 24). His memorandum, mordantly titled “The Anti-Semitism of the Present Government,” accused ministers of pursuing a policy that would “prove a rallying ground for anti-Semites in every country in the world.” He wrote with a personal urgency rare in Cabinet prose:

“I assert that there is not a Jewish nation.”

“Palestine will become the world’s Ghetto.”

Endorsing Zionism, he warned, would recast a Jew like himself—Britain’s India Secretary—as “at best... a naturalized foreigner” (Schneer, ch. 24).

Montagu feared that creating a “national home” would delegitimize Jewish belonging in Britain and elsewhere. He had, he said, “been trying all [his] life to escape the ghetto,” only to see fellow Jews, abetted by the government, “push him back inside.” It was not a theoretical worry; it was a protest from a Cabinet minister who believed the policy would strip him of political credibility at the India Office (Schneer, ch. 24).

Montagu’s dissent stalled the process. On 3 September 1917 the War Cabinet met without Lloyd George or Balfour and heard Milner, Amery, and Lord Robert Cecil argue for the Zionist phrasing while Montagu pressed the case against it. The compromise was a decision to delay and to consult U.S. President Woodrow Wilson before moving forward (Schneer, ch. 24). Weizmann counter-lobbied ferociously, mobilizing Justice Louis D. Brandeis and Colonel Edward M. House in Washington, orchestrating telegrams from synagogues across Britain, and keeping pressure on Whitehall through Lord Rothschild (Schneer, ch. 24).

Cabinet Deliberations

When the War Cabinet reconvened on 4 October, George Nathaniel Curzon, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston—former Viceroy of India and now Lord President of the Council—intervened against Zionism from a different angle: practical feasibility. Having visited Palestine, he called it “barren and desolate,” doubted large-scale immigration or economic capacity, and asked what would become of the Muslim majority. He warned that Arabs “will not be content either to be expropriated for Jewish immigrants or to act merely as hewers of wood and drawers of water” (Schneer, ch. 24). Curzon’s argument cooled the room, but it did not tip the scales. As he admitted, there were “diplomatic arguments”: officials believed that a declaration would help Allied propaganda among Jews in Russia and America and pre-empt rumored German courting of Zionists (Schneer, ch. 24).

Those rumors mattered. Weizmann and others had indeed warned British officials that Germany and the Ottomans were exploring pro-Zionist gestures. Reports filtered in of articles by the Bavarian Major Franz Carl Endress and of meetings allegedly involving Richard von Kühlmann and Ahmed Cemal Paşa; Count Johann von Bernstorff was said to be sounding out Jews in Constantinople and Bern (Schneer, ch. 24). British officials leapt to a conclusion historians do not share: that the Central Powers could meaningfully deliver for Zionism. The result, Schneer argues, was a decision shaped by inflated beliefs about both German leverage in Constantinople and the “international power of the Jews” (a phrase scrawled by Lord Robert Cecil on a Foreign Office document early in the war) (Schneer, ch. 24).

On 31 October 1917, with Wilson now supportive, the War Cabinet approved a letter to Lord Rothschild. The published text (dated 2 November) favored “a national home for the Jewish people,” pledged “best endeavours,” and added two safeguards: nothing would prejudice “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” or “the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country” (Schneer, ch. 24). That last clause answered Montagu directly. It did not persuade him. Writing soon after he reached India, he called the decision “an irreparable blow to Jewish Britons,” and dismissed the government for trying “to set up a people which does not exist” (Schneer, ch. 24).

Schneer’s reconstruction does not end at the moment of triumph. He shows how precarious the Declaration remained in the months after publication. Even as Weizmann celebrated, senior ministers were testing a separate peace with the Ottoman Empire—a “third option” that could have left the Ottoman flag flying over Palestine under arrangements “on Egyptian lines,” that is, symbolic Ottoman sovereignty and British control akin to the pre-1914 “veiled protectorate” in Egypt (Schneer, ch. 25). Here Schneer is at his most unsettling. He tracks a thicket of secret feelers: Rahmi Bey, the vali (governor) of Smyrna; intermediaries in Athens and Switzerland; Sir Horace Rumbold; Jan Smuts; and above all the arms dealer Basil Zaharoff engaging with Enver Pasha via an emissary named Abdul Kerim (Schneer, ch. 25).

The Fragile Victory

The internal British record was contradictory. The Foreign Office (Balfour and Graham) warned that allowing the Turkish flag over Palestine would look like treachery to Zionists; cables went out saying no flag (Schneer, ch. 25). Yet Lloyd George, in personal instructions carried through Zaharoff, authorized assurances that the flag could indeed remain over Palestine, as the price of detaching Turkey from Germany (Schneer, ch. 25). The same Prime Minister who had shepherded the Balfour Declaration was, within weeks, prepared to compromise its practical meaning if it hastened victory. Nothing came of these feelers—Enver wavered; the Russian front collapsed; General Edmund Allenby entered Jerusalem—but Schneer’s point is clear: the Declaration “just missed the side track” (Schneer, ch. 25).

This contingency matters for how we read Edwin Montagu. He was not a Zionist assimilationist quibbling over abstractions. He grasped, earlier than most, that declaring Jews a nation with a home elsewhere could be seized upon to question Jews’ status here. In his words, endorsing Zionism would “vitally prejudice the position of every Jew elsewhere” (Schneer, ch. 24). The Cabinet added the second safeguard clause largely because of him. That he remained unconvinced is part of the Declaration’s moral dossier, not its footnote.

Schneer then draws the threads tighter. The war had produced overlapping and often incompatible promises. Sir Henry McMahon’s ambiguous correspondence with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, the Sykes–Picot plan for an international regime in Palestine while dividing the rest of the Levant, the Zionist pledge in Balfour’s letter, and Lloyd George’s brief flirtation with Ottoman suzerainty in exchange for a separate peace all pointed to Palestine as what Schneer calls a land “promised” four times (Schneer, ch. 26). Each promise was animated by Britain’s larger aims: defeat Germany; keep France in the war and, later, settle a postwar balance in the Middle East; and exploit what British officials believed to be decisive currents of Jewish opinion in Russia and America (Schneer, ch. 26).

The aftermath followed the logic of those contradictions. Arabs and Muslims reacted swiftly. Syrian notables warned Balfour that Palestine was the “heart” of Syria and sacred to Islam and Christianity as well as to Judaism; London’s Islamic Society and figures like Syed Ameer Ali protested that placing Muslim shrines under Jewish control would be intolerable (Schneer, ch. 26). British officials shrugged, pointing again to the protective language; some, like General Gilbert Clayton, went further, invoking Zionist power—“the Jews controlled the capital... they would undoubtedly succeed”—and advising Arabs to accommodate the new reality (Schneer, ch. 26). The seeds of distrust were sown. Under the Mandate after 1920, with Herbert Samuel as the first High Commissioner, suspensions of immigration after riots, the Passfield White Paper (1930), the Peel Commission (1937), and the 1939 White Paper all kept altering expectations. Zionist–British relations frayed; Arab–British relations curdled; Jewish–Arab relations bled (Schneer, ch. 26).

Repercussions in the Middle East

Schneer’s final image is classical: Britain slew the Ottoman dragon and sowed dragon’s teeth. Men armed rose from the ground (Schneer, ch. 26). That harvest, he suggests, grew from the process that produced the Balfour Declaration—“inspired opportunism” by Weizmann; duplicity and improvisation by British officials; misunderstandings and wishful thinking by all parties; and, not least, the internal British argument about what it meant to be a Jew in Britain. On that last question, Edwin Samuel Montagu remains the hinge. He did not speak for all British Jews, and he did not stop the Declaration. But his dissent forced the Cabinet to acknowledge in the text itself that Jews were citizens where they lived and that nothing in Balfour’s promise should threaten that status.

“I assert that there is not a Jewish nation,” he wrote, because to assert otherwise would place him, and Jews like him, in a foreign category at home (Schneer, ch. 24).

Whether history vindicated Montagu depends on where one looks. Antisemitism rose and fell in different places for reasons not governed by Britain’s wording in 1917; the State of Israel eventually emerged; the question of Jewish belonging in Britain did not vanish. Schneer’s contribution is to show that none of this was inevitable. The Declaration that bears Balfour’s name could have been blunted by a separate peace; it could have been reshaped by different drafts or different lobbyists; it might have come wrapped in international control rather than British tutelage. It came as it did because of a specific alignment of pressures and beliefs in the summer and autumn of 1917—and because one Jewish minister warned that the cost would be paid at home. That, too, is part of what the Balfour Declaration declared.

The Legacy of Guilt

Seen in retrospect, the Balfour Declaration was never a mere diplomatic communiqué; it was the moral expression of an imperial worldview that bound pity to power. The men who drafted and approved it—Balfour, Lloyd George, Cecil, and Milner—believed Britain could atone for Europe’s long history of anti-Semitism by transforming guilt into policy abroad. But their sympathy for Jews carried hierarchy within it. The Jews were to be restored to the Holy Land under British supervision, their redemption doubling as proof of British benevolence.

This was philo-Semitism as policy: admiration fused with fear. But also philanthropy serving empire. The same paternal instinct that produced the 1905 Aliens Act, closing Britain’s ports to Jewish refugees, produced a declaration opening Palestine to them.

In that gesture lay a deeper psychological transaction. Europe’s governing classes had come to feel the weight of their own moral failure as they tolerated the pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe that scarred Jewish life from the 1880s through the early 1910s (notably in Odessa, Kishinev), maintained social barriers, and quietly endorsed prejudice. The Balfour Declaration displaced that burden onto the geography of empire. By granting Jews a “home” elsewhere, Britain imagined itself absolved, its conscience cleansed without social reform. The political question of Jewish belonging shifted from Europe to the Middle East, where it acquired new victims and new forms. The displacement was not territorial alone; it was moral. Guilt that might have reformed Europe’s civic life instead nourished a fantasy of moral trusteeship abroad.

A century later this fantasy continues to shape Western policy. The same nations that once treated Jews as outsiders now present unwavering support for Israel as the highest proof of liberal virtue. In moments of crisis such as Lebanon in 1982 or Gaza in 2008, 2014, and 2023, the reaction follows the same pattern. Israel’s actions are seen as the continuation of Europe’s own redemption. “Never again,” once a vow of universal vigilance, has turned into a justification for silence. The rhetoric of Israel’s “right to defend itself” echoes Balfour’s paternal language and casts violence as civilisation’s necessary work. Through this conversion of guilt into permission, sympathy becomes complicity.

Edwin Samuel Montagu’s solitary protest therefore reads as something greater than a footnote to 1917. It stands as a mirror to the present. He saw how good intentions, when mixed with racial myth and imperial power, could reproduce the injustices they claimed to cure. His insistence that Jews remain citizens where they live, and that equality rather than nationhood defines emancipation, feels prophetic and tragic at the same time. The Balfour Declaration promised deliverance yet performed displacement. Its afterlife, from Mandate to Gaza, shows how Europe’s unexamined guilt still seeks absolution in the suffering of others. Until that inheritance is faced squarely, the line from London to Jerusalem will remain unbroken. This is a century-long attempt to heal the wounds of the West upon other people’s - Palestinian- bodies.