The Man of the Hour: Ahmad al-Sharaa

So much converges on him. The success of one of the hardest post-war transitions in recent history may hinge on his ability to manage it. Who is he and can he do it?

When photos of Ahmad al-Sharaa’s brief but landmark meeting with Donald Trump and Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh were released to the press, the internet lit up with incredulous commentary. “I want to see this guy’s diary,” someone wrote. Others joked: “Try time-travelling 10 years back and explaining this picture to your past self.”

But perhaps the most telling comment came from a Middle East professor:

“Imagine someone in 2014 telling you that this photo would be real: MBS was a minor royal, Trump was still The Apprentice guy, and al-Sharaa was an al-Qaeda commander.”

The trajectories of Trump and MBS are well known. The same cannot be said of Ahmad al-Sharaa (formerly known as al-Jolani), whose life remains a puzzle with missing pieces. I will now attempt to gather the fragments1 we do know.

1. What are the words most often used to describe him?

Jihadist. Terrorist. Islamist. Pragmatist. Clever. Enigma. Chameleon. Pretender. Contradiction. Shy. Authoritarian. Power-seeker. Shapeshifter. Charismatic. Tall. Fighter. Quiet.

2. Where does he come from, and why is his father a pivotal figure?

Al-Sharaa’s father, Hussein al-Sharaa, is a towering presence in his son’s story, an austere, intellectually exacting Arab nationalist who played a defining role in Ahmad’s formation. When Hussein visited Ahmad at the presidential palace for the Eid celebrations, it was a moment not of triumph but of deference. Ahmad leaned forward and kissed his father’s hand. Just weeks earlier, Hussein al-Sharaa posted a public critique of his son’s economic policies on Facebook, an act that laid bare the unyielding, almost immovable hierarchy between father and son.

The family hails from Fiq, a town in the Golan Heights once dubbed the “Decision Capital.” They claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad and once owned nearly 85% of Fiq’s land, including olive groves in Wadi Masoud. After the 1967 war, they lost everything and moved to a suburb on the outskirts of Damascus, where displacement carried both social and psychological weight.

Father Hussein’s political life was defined by resistance and reinvention. He was arrested at 19, exiled to Jordan and then Iraq, where he studied economics and political science. It was there that he developed a deep admiration for Saddam Hussein, whom he saw as a voice of Sunni Arab dignity. In his 2022 book A Reading of the Revolutionary Resurrection, he mourned the fall of Baghdad as the end of an assertive Arab order. Despite acknowledging Saddam’s authoritarianism, he lamented the collapse of Arab sovereignty.

Upon returning to Syria in the 1970s, Hussein was again imprisoned. He later worked as a teacher in Daraa, won a council seat in Quneitra, and published several studies on oil and development. He left for Saudi Arabia in 1979, where he became a senior oil economist and adviser.

Ahmad al-Sharaa was born in Riyadh in 1982 and spent his early childhood there, immersed in a milieu that was both religious and technocratic. His father worked for the Saudi oil ministry and authored several studies on Arab oil economies.

In 1989, the family returned to Damascus when Ahmad was six, after his father managed to rehabilitate ties with the regime and eventually became an adviser to the prime minister. They settled in Mezzeh East Villas, a plush enclave reserved for regime loyalists. Yet despite their material comfort, they remained outsiders.

Ahmad’s adolescence was marked by silence and social dissonance. He was described as shy, reserved, and acutely self-conscious about his rural Golan roots and his parents’ accents. (He now speaks with an impeccable Damascene accent but can also imitate other dialects—particularly the Iraqi one—when needed.) Neighbors recalled a boy who avoided eye contact and mumbled responses. In a Damascus elite school, surrounded by Alawite and Christian classmates, he didn’t quite belong. He was also bullied. This mismatch between appearance and aspiration may have planted the first seeds of rupture.

Father Hussein’s refusal to authorise corrupt financial transfers eventually led to his dismissal from government. Realizing there would be no reconciliation with the regime, he opened a real estate agency and a grocery shop, where Ahmad occasionally helped rent apartments to regime loyalists. That experience of witnessing sycophancy and corruption firsthand, left Ahmad embittered.

3. How did he become an Islamist in a secular nationalist family?

Though schooled among a secular, interfaith elite, Ahmad remained on the margins. He later enrolled in a media studies program, something his father disapproved of and dismissed, as he had expected his son to pursue a more intellectually rigorous path.

Ahmad’s religious turn came in his late teens, during the Second Intifada 2000-2005. He described being moved by the suffering of Palestinians, leading him to prayer and mosque life. He began frequenting al-Shafi’i mosque, seeking answers on Palestine, found instead a total religious life. He adopted Salafi dress, grew austere in demeanor, and even chastised the local imam for failing to cover his head.

This turn deepened with proximity to Khaled Meshal, Hamas’s Damascus-based leader. By 9/11, he was captivated by Osama bin Laden, not for theology, but for having “humbled a superpower.”

4. Why does his road to jihadism pass through Iraq?

By 2003, he answered the call to defend Iraq against the U.S. invasion. His family had no idea where he had gone.

His first stint in Iraq was brief and chaotic. Disillusioned by the fall of Saddam and likely unprepared for the realities of war, he returned to Syria, only to be arrested by the mukhabarat. He escaped harsh punishment by claiming ignorance and was released. But he was now persona non grata at home—his secular father threw him out. He moved in with his maternal relatives in a working-class district, where displaced rural families like his own were clustered, and radicalism was brewing.

By 2005, he returned to Mosul using false IDs and a fluent Iraqi accent. He joined the Mujahideen Shura Council, later part of al-Qaeda(AQ) in Iraq under Zarqawi. Some say he was a recruiter, others a bombmaker. He was captured in 2006 and spent five years in Camp Bucca, US military-run detention centre in Iraq. There, he rose to prominence. Rejecting the Baathist-run prison emirates, he taught what he called the "correct" jihad. Inmates began joining his wing. One would later recommend him to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the founder of ISIS.

5. How did he rise within al-Qaeda and establish himself in Syria?

Released in 2011, he authored “The Support Front to the People of the Levant” which was a blueprint for jihad in Syria. Baghdadi gave him funds and men to found AQ’s Syrian affiliate which then became Jabhat al-Nusra. Al-Nusra’s early attacks in Aleppo and Damascus signaled tactical precision and demonstrated that he built an efficient, locally embedded jihadist network.

In 2015, al-Zawahiri instructed him to “localize”: embed with the revolution, form alliances, build a Sharia court, and avoid attacks on the West. Jolani hesitated. In a televised interview, he insisted their focus was Assad but warned that continued U.S. attacks could force a response.

Internally, these shifts led to friction and defections.

As infighting ravaged the jihadist ecosystem, al-Sharaa split from ISIS, aligned briefly with al-Qaeda, then broke off again to form Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). By 2017, he had eliminated rival factions and ruled Idlib. Scholars call this trajectory from global jihad to local governance a textbook case of “downward scale-shift”.

6. How did he rule Idlib and transform his movement?

From 2017, al-Sharaa consolidated control of Idlib, defeating rivals like Ahrar al-Sham, seizing key border crossings, and forming the Salvation Government. It operated as a hybrid: part militia, part state. It resembled a war economy: taxation, trade, policing.

Ministries and courts were formed, but, surely, real authority remained informal and vertical. His security forces were better organized and less corrupt than most rebel outfits. Gradually, HTS even changed its legal school of jurisprudence and softened its treatment of minorities. Churches were restored. Foreign NGOs resumed operations. Electricity flowed from Turkey. A Luxembourg-coded mobile network was set up.

Though still authoritarian, it became Syria-focused, offering services, security, and relative stability. Western intelligence quietly acknowledged its utility.

7. How did he topple Assad and take power in Damascus?

By 2024, the axis backing Assad was faltering. Jolani launched Operation Deterrence of Aggression. Contrary to what Trump insinuated, it was not a Turkish operation. In fact, when Turkish intelligence got wind of the plan, they attempted to stop it, fearing it would trigger further instability and another wave of refugees into Turkey. Ankara even alerted the Russians, prompting the first Russian airstrike in six months. Still, no one expected Aleppo to fall so quickly. HTS forces swept through Aleppo and Damascus with astonishing speed. Assad fled. HTS took the People’s Palace.

In victory, Jolani became Ahmad al-Sharaa again. He announced a transitional phase, constitutional reform, and power-sharing. Shock and disbelief followed. In Damascus shops, Assad portraits and statues were taken down.

8. Why do people trust him, and how does he persuade?

Whether it’s suicide bombers, tribal elders, or diplomats, everyone who meets him comes away impressed. A chameleon in speech and bearing, al-Sharaa adapts to Islamist, nationalist, or technocratic registers with ease.

Of course, being a skilled persuader matters. But al-Sharaa also needs a circle of aides who can provide him with accurate, strategic information—and that, so far, appears to be lacking. The most capable figure in that regard is his foreign minister, Assad al-Shaibani who has done his studies in Istanbul. Yet the small piece of paper he clutched during the high-stakes meeting with MBS and Trump said it all: he needs a more professional team. His instincts and charisma may carry him far, but both have their limits

9. What do we know about his personal life and image?

For years, nothing. But in early 2025, he appeared with his wife, Latifa al-Sharaa (Droubi), during an event with Syrian women in exile. The gesture was widely interpreted as an effort to signal visibility and legitimacy within Syria’s new leadership. The couple reportedly has three children. Their first public appearance together was during an official visit to Riyadh in early 2025, where they performed the Umrah pilgrimage that marked a carefully staged debut onto the international stage. Her first official appearance was in Turkey, where Emine Erdoğan hosted her warmly.

Can he do this?

He faces a diplomatic Rubik’s cube. He must navigate between:

Israel, which sees his rise as both a threat and an opportunity. He refers to Israel as ‘Israeli state’ rather than the Assad-era designation of 'Zionist entity' or ‘occupying power’ and this has unsettled Islamists and emboldened normalization advocates. But Israel’s security establishment remains unconvinced, stepping up covert operations near the Golan and in southwest Syria to test his red lines.

Turkey, the power broker that helped enable his transformation him from pariah to provisional partner. Turkey put all his diplomatic clout for the lifting of sanctions and pushed for his inclusion in regional talks. Yet their support carries strings of an economic, intelligence, and territorial nature, along with a host of implicit demands. Sharaa relies on Turkish expertise and infrastructure but must not appear subservient.

The Syrian Kurds, whose disciplined militias surpass HTS in strength. Any post-war settlement will depend on his ability to forge a modus vivendi with them. That likely means endorsing a form of Kurdish autonomy and that is anathema to Turkey and parts of his own base. If he cannot bridge this divide, he risks permanent instability.

The Gulf monarchies, who watch him with a mixture of interest and alarm. His Islamist past stirs unease in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, which have spent years dismantling political Islam at home and abroad. But his pragmatism could win over skeptical royals if managed carefully. He must signal continuity with the region’s new authoritarian normal without appearing as a revolutionary export.

He cannot afford to alienate any. He must be Islamist enough to keep internal cohesion, secular enough to reassure foreign donors, nationalist enough to placate the Arab street—but not so much that Gulf capitals grow wary.

It is another irony that after becoming the de facto president of Syria, he visited the very mosque where his Islamist formation began—al-Shafi’i mosque—and declared that “the West has nothing to fear from Syria.”

His timid response to Israel’s provocations in Syria and the ongoing genocide in Gaza, along with his recent hint at joining the Abraham Accords during his meeting with Trump, has already triggered backlash from jihadist circles. Some jihadi clerics and ISIS have openly labeled him an apostate.

Trump claimed that he asked Erdoğa whether al-Sharaa could walk this tightrope. Erdoğan’s reply was simple: “I believe he can.” Shall we take their word for it. Maybe they saw something familiar in him. Who knows.

The ultimate question is : Can this shapeshifting man hold the center, crowded as it is with complexity and traps? Perhaps his ability to adapt is his greatest asset. Who know.

But if this were a film about a man who once dressed and acted like Osama bin Laden, now negotiating with a former real estate mogul turned U.S. president guilty of 34 felony counts, while standing beside a Gulf prince whose entourage once flew to a foreign country to dismember a dissident journalist at the consulate premises, we’d have rated it five out of ten on IMDb for lack of plausibility. Just think about the world we live in.

And yet, here we are.

PKK’s disarmament on the table

Two significant meetings took place this week, almost in parallel—one in Washington, the other in Damascus. In the U.S. capital, a new round of the Syria Working Group convened, bringing together American and Turkish interagency delegations led by Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau and Turkish Deputy Foreign Minister Dr. Nuh Yılmaz. The official readout stated: “The delegations discussed shared priorities in Syria, including sanctions relief per President Trump’s directive and combating terrorism in all its forms. The United States and Türkiye share a vision of a stable Syria, at peace with itself and its neighborhood, enabling the return of millions of displaced Syrians. Both sides reaffirmed their commitment to Syria’s territorial integrity and to preventing the country from becoming a safe haven for terrorist groups.”

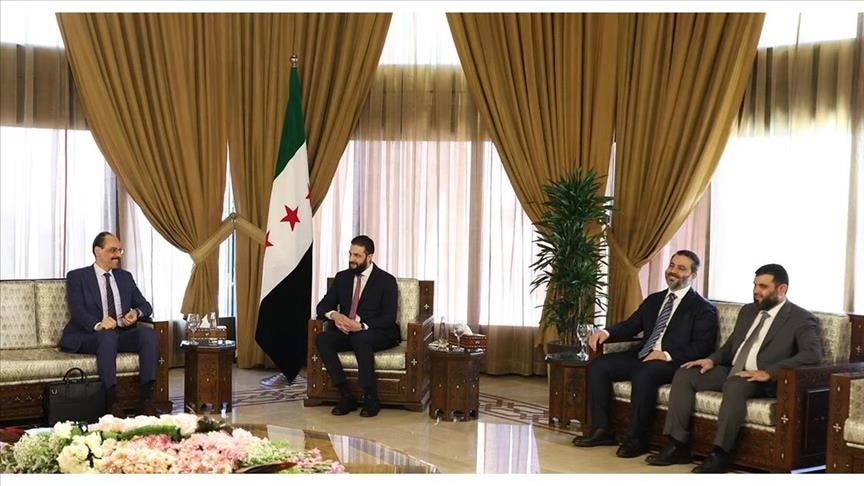

Meanwhile, in Damascus, Turkish intelligence chief İbrahim Kalın met with Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa, Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaibani, and intelligence chief Hussein al-Salama. According to Turkey’s state news agency, ‘the discussions centered on bilateral ties, Syria’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, and political stabilization. Crucially, they also addressed the disarmament and reintegration of armed groups including the PKK/YPG into Syria’s new political and military framework, alongside border security, the operation of customs gates, and the transfer of ISIS detention sites to Syrian control.’

The central issue in both meetings was the future of Kurdish forces in Syria. With the PKK’s recent announcement of disbandment, Ankara appears to be moving to the next phase, even though the Kurdish side states that they await legal guarantees before surrendering arms. These talks suggest a coordinated effort to fold the SDF/PYD into the Syrian army, with American and Turkish oversight. Simultaneously, Turkey is in talks with Baghdad and the KDP to establish a joint oversight mechanism in northern Iraq, to be run through Turkish intelligence (MİT).

Great write-up. I have made the assertion many times over the past few months that Al-Sharaa is a top contender for the title of 'the world's most interesting man'. He is also undoubtedly a remarkably talented politician - as you note, nobody comes away from meeting him unimpressed. I've also been told that he speaks Fusha/MSA beautifully, which helps with his status as a persuasive rhetorician!

why you didn't mention that during his idlib experience there were protests against him because hts taxed displaced people or tortured prisoners there were opposition from other militias who he eliminated also his now public safety or new syrian army is a merge of all militia factions some of them have ISIS terrorist nature and are policing people or cause sectarian violence against alawites